Figure 1 – Scene from Alcoa film “Unfinished Rainbows” From left, Miss Moses, Matthew Griswold and Arthur Davis

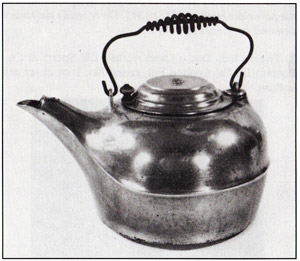

Griswold Aluminum Tea Kettle was most likely made by the Pittsburgh Reduction Company.

Although the uses of aluminum, at least in its solid metallic form, had remained elusive prior to the 19th century, uses of aluminum silicates for pottery and “alums” for vegetable dyes and medicines had been traced back to ancient Egypt and Persia. The reduction or smelting of pure metallic aluminum from its oxide-bound state confounded some of the best scientific minds of the ninth and tenth century.

In the nineteenth century, aluminum had been reduced chemically to its metallic form in minute amounts, but cost was prohibitive, exceeding $500 a pound, more than twice the value of gold or platinum. In the 1850s aluminum tableware adorned the banquet table of the Court of France, and became a fashionable substance for jewelry – more fashionable than gold or silver.

By 1857, French scientist Henri Sainte Claire Deville had succeeded in obtaining metallic aluminum chemically while reducing the cost to $17 a pound.

Despite technical improvements and their corresponding reductions in cost, aluminum remained a craftsman’s material, luxurious and semi-precious. By the end of 1887, remarkable advances in processing helped bring the American price down to $8 a pound. This was still too high for mass consumption. The accumulated total of world-wide aluminum production since 1854 was probably under 140,000 pounds, mostly produced in the 1880s. Applications ranged from jewelry and other small personal items to more functional but still luxurious uses in navigation instruments, balances and clocks. One hundred ounces of aluminum capped the Washington Monument, where the metal served as both ornament and a lightning rod in 1884.

Suddenly, a technical revolution occurred, displacing the chemical methods of making pure aluminum by a cheaper and drastically different means of production that would make the earths most common metal available for mass market.

The same year the Washington Monument was capped with aluminum, a young scientist, Charles Martin Hall, discovered an electrolytic process to smelt aluminum which could significantly reduce its cost while experimenting in a makeshift laboratory in the woodshed of his kitchen in Oberlin, Ohio.

After patenting his discovery, he approached a group of eight investors with his proposal and beliefs in the future of aluminum. On July 31, 1888, these investors, all experts in steel, all connected in one way or another with an industry that was becoming the linchpin to Pittsburgh’s development, met to discuss the possibilities of aluminum. Eight days later, six of the eight agreed to stake the trial development of the new process. On November 29th, 1888 the new company, The Pittsburgh Reduction Company, poured its first aluminum ingot at a production cost of $2 a pound.

Within months, Hall’s invention was developed into commercial production. The company’s business strategy was to sell aluminum in ingot form to manufacturers to remelt and cast into their specialty products. Typical of anything so new and untried, convincing manufacturers to invest in and use this new metal proved difficult. About 1894, the Pittsburgh Reduction Company sent their young salesman, Arthur Davis, to Erie, Pennsylvania to convince Matthew Griswold of the Griswold Mfg. Company to try casting aluminum products from aluminum he could purchase from the Pittsburgh based firm. The Griswold aluminum tea kettle was born.

Davis was to convince Matthew Griswold that the much lighter metal would be better than iron for cookware. Miss Moses, Matthew Griswold’s secretary, is alleged to have said that the aluminum would be wonderful for Griswold aluminum tea kettles, “so light and clean-looking.” (Figure 1)

Although it was salesman Davis’s goal to sell the Griswold Mfg. Co. aluminum ingots, Matthew Griswold would have no part of it. He was interested in the concept of Griswold Aluminum Tea Kettles but was not going to disturb his manufacturing process to convert to casting aluminum. The salesman was in a dilemma. The Pittsburgh Reduction Company did not have a foundry nor the technology for casting individual pieces—they cast ingots. Rather than lose the sale, Davis agreed that if Matthew Griswold would lend the Pittsburgh Reduction Company a molder to assist them, they would cast a sample Griswold Aluminum Tea Kettle.

Some time later when the Pittsburgh Reduction Company salesman returned to Erie with the sample aluminum tea kettles, Matthew Griswold was impressed and

Figure 2 – Griswold Aluminum Tea Kettle

responded by ordering two thousand aluminum tea kettles. Salesman Davis balked—the agreement was to cast the samples. His company did not want to get into the cookware business, but Matthew Griswold stood firm.

It was important to the Pittsburgh Reduction Company to get aluminum into the consumer market. These Griswold aluminum teakettles would be one way to accomplish it. Davis agreed to the order of two thousand aluminum tea kettles.

Although historical records are sketchy, it appears that the aluminum tea kettle in Figure 2 is the style that was cast. This style is nearly identical to the iron tea kettles (Figure 2) of that period as is the marking “ERIE” on the cover. This is also the style used in the Alcoa promotional movie, “Unfinished Rainbows”, although Alcoa admits they have no documentation that this was the aluminum tea kettle. After delivery of the original aluminum tea kettles, and obvious successful sales, the Griswold Mfg. Co. agreed to purchase aluminum ingots from the Pittsburgh Reduction Company (renamed Alcoa in 1907) and to do their own aluminum casting.

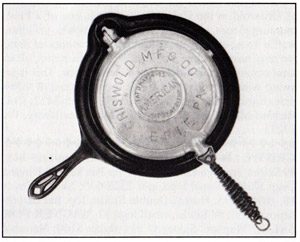

Was the tea kettle the first and last piece cast by Alcoa for Griswold? Probably not. In fact, it appears that Griswold did iron castings for Alcoa, perhaps on an exchange basis. (Figure 3) The aluminum waffle iron in Figure 3 has a very unusual handle, light weight wire wrapped around a steel handle which in turn is riveted to the waffle paddle.

Figure 3 – Griswold Aluminum Waffle Iron

This handle is not typical with Griswold. The waffle iron does sit on a typical Griswold iron base, however. The patent date of May 14, 1901 on the waffle iron reflects the patent of the (acorn) hinge, patented by Griswold. This style waffle iron is usually found marked “Wear Ever.” Wear Ever was the brand of the Aluminum Cooking Utensil Company, a wholly owned subsidiary of Alcoa created to sell Alcoa produced aluminum cookware. The Wear Ever waffle iron sits on an iron Griswold base. How ironic! By 1909, Alcoa was the third largest aluminum cookware producer in the U.S. One has to ask, would Alcoa have entered the cookware market if it had not been unwittingly forced by Matthew Griswold to do so in order for them to market their new product, aluminum?

Want to clean your Griswold Aluminum Tea Kettle? Aluminum Restoration

The Griswold Aluminum Tea Kettle on Ebay

Read about the Griswold Aluminum Toy Griddle

References: From Monopoly to Competition, Cambridge University Press 1988; Saturday Evening Post, Feb. 1949, Unfinished Rainbows, Wilding Pictures c.1945

Wagner Ware aluminum toy handle griddle

Wagner Ware aluminum toy handle griddle Wagner Ware aluminum toy handle griddle submitted by Jimmy Gilmore of Lorenzo, Texas. The toy griddle measures about 4

Griswold Aluminum Tea Kettle: Not Made By Griswold!

Griswold Aluminum Tea Kettle was most likely made by the Pittsburgh Reduction Company. Although the uses of aluminum, at least in its solid metallic form,

Griswold Manufacturing Vintage Warranty Letter

Griswold Manufacturing Vintage Warranty Letter response from January 5th 1925 Bailed Griswold griddles were hung directly over coals, on a oven rack, directly over a